Cyclical Vision: VAMO Proposes an Alternative to Architectural Permanence

At the 19th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, curated by MIT Professor Carlo Ratti, a collaboration between ETH Zurich, MIT, MAD, and partners showcases the potential of biodegradable reclaimed materials and structural strategies of tension and compression.

By Matilda Bathurst

Jun 16, 2025

The International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia holds up a mirror to the industry — not only reflecting current priorities and preoccupations, but also projecting an agenda for what might be possible.

Curated by Carlo Ratti, MIT professor of practice of urban technologies and planning, this year’s exhibition (“Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective”) proposes a “Circular Economy Manifesto.”

Image: Adélaïde Zollinger

Curated by Carlo Ratti, MIT professor of practice of urban technologies and planning, this year’s exhibition (“Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective”) proposes a “Circular Economy Manifesto” with the goal to support the “development and production of projects that utilize natural, artificial, and collective intelligence to combat the climate crisis.”

Designers and architects will quickly recognize the paradox of this year’s theme. Global architecture festivals have historically had a high carbon footprint, using vast amounts of energy, resources, and materials to build and transport temporary structures that are later discarded. This year’s unprecedented emphasis on waste elimination and carbon neutrality challenges participants to reframe apparent limitations into creative constraints. In this way, the Biennale acts as a microcosm of current planetary conditions — a staging ground to envision and practice adaptive strategies.

VAMO (Vegetal, Animal, Mineral, Other)

When Ratti approached John Ochsendorf, MIT professor and founding director of MIT MAD, with the invitation to interpret the theme of circularity, the project became the premise for a convergence of ideas, tools, and know-how from multiple teams at MIT and the wider MIT community.

MIT Digital Structures research group, directed by Professor Caitlin Mueller, applied expertise in designing efficient structures of tension and compression. The Circular Engineering for Architecture research group, led by MIT alumna Catherine De Wolf at ETH Zurich, explored how digital technologies and traditional woodworking techniques could make optimal use of reclaimed timber. Early-stage startups — including companies launched by the venture accelerator MITdesignX — contributed innovative materials harnessing natural byproducts from vegetal, animal, mineral, and other sources.

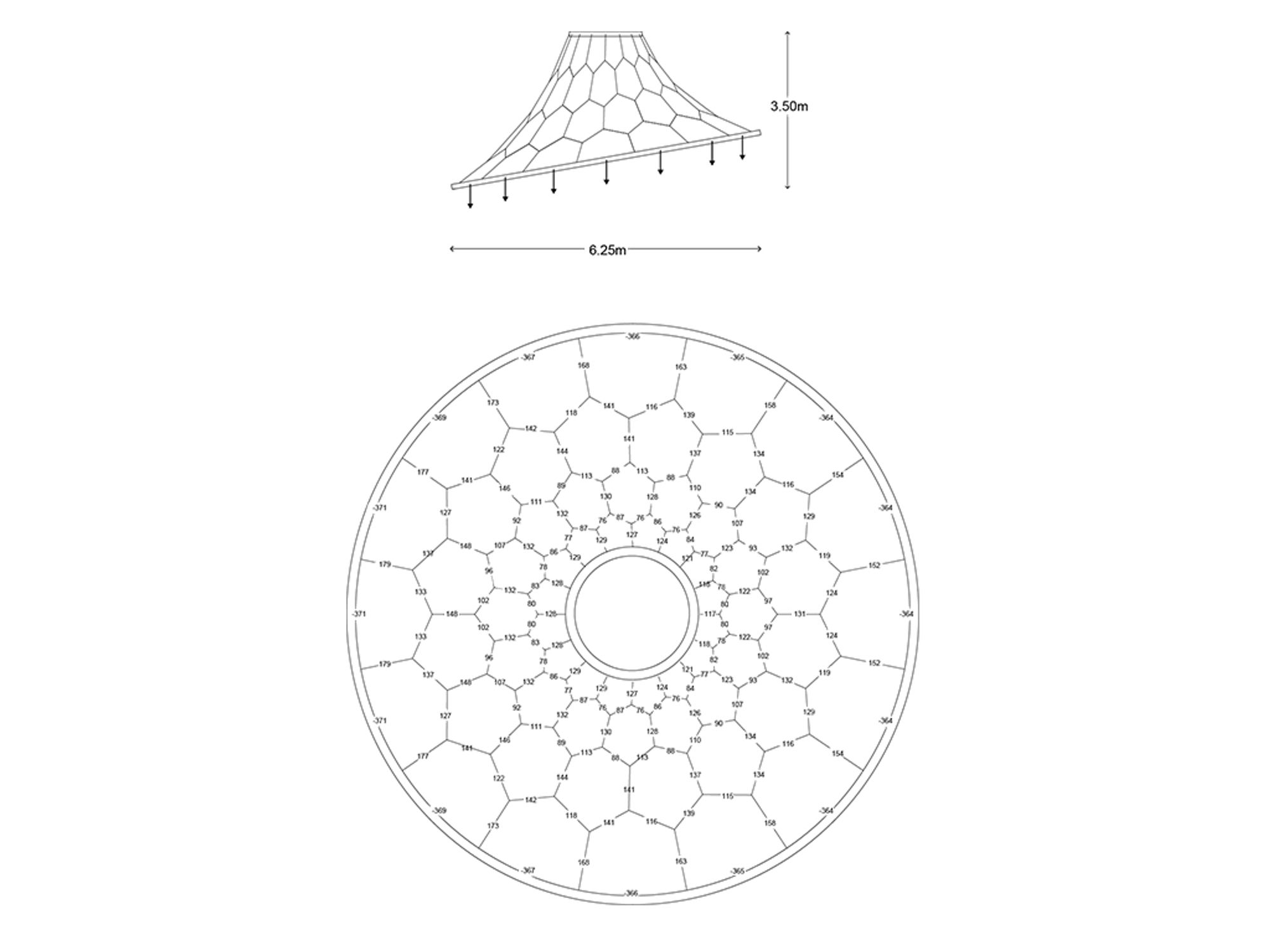

The result is VAMO (Vegetal, Animal, Mineral, Other), an ultra-lightweight, biodegradable, and transportable canopy designed to circle around a brick column in the Corderie of the Venice Arsenale – a historic space originally used to manufacture ropes for the city’s naval fleet.

“This year’s Biennale marks a new radicalism in approaches to architecture,” said Ochsendorf. “It’s no longer sufficient to propose an exciting idea or present a stylish installation. The conversation on material reuse must have relevance beyond the exhibition space, and we’re seeing a hunger among students and emerging practices to have a tangible impact. VAMO isn’t just a temporary shelter for new thinking. It’s a material and structural prototype that will evolve into multiple different forms after the Biennale.”

Tension and Compression

The choice to build the support structure from reclaimed timber and hemp rope called for a highly efficient design to maximize the inherent potential of comparatively humble materials. Working purely in tension (the spliced cable net) or compression (the oblique timber rings), the structure appears to float — yet is capable of supporting substantial loads across large distances. The canopy weighs less than 200 kg and covers over 6 meters in diameter, highlighting the incredible lightness that equilibrium forms can achieve. VAMO simultaneously showcases a series of sustainable claddings and finishes made from surprising upcycled materials — from coconut husks, spent coffee grounds, and pineapple peel, to wool, glass, and scraps of leather.

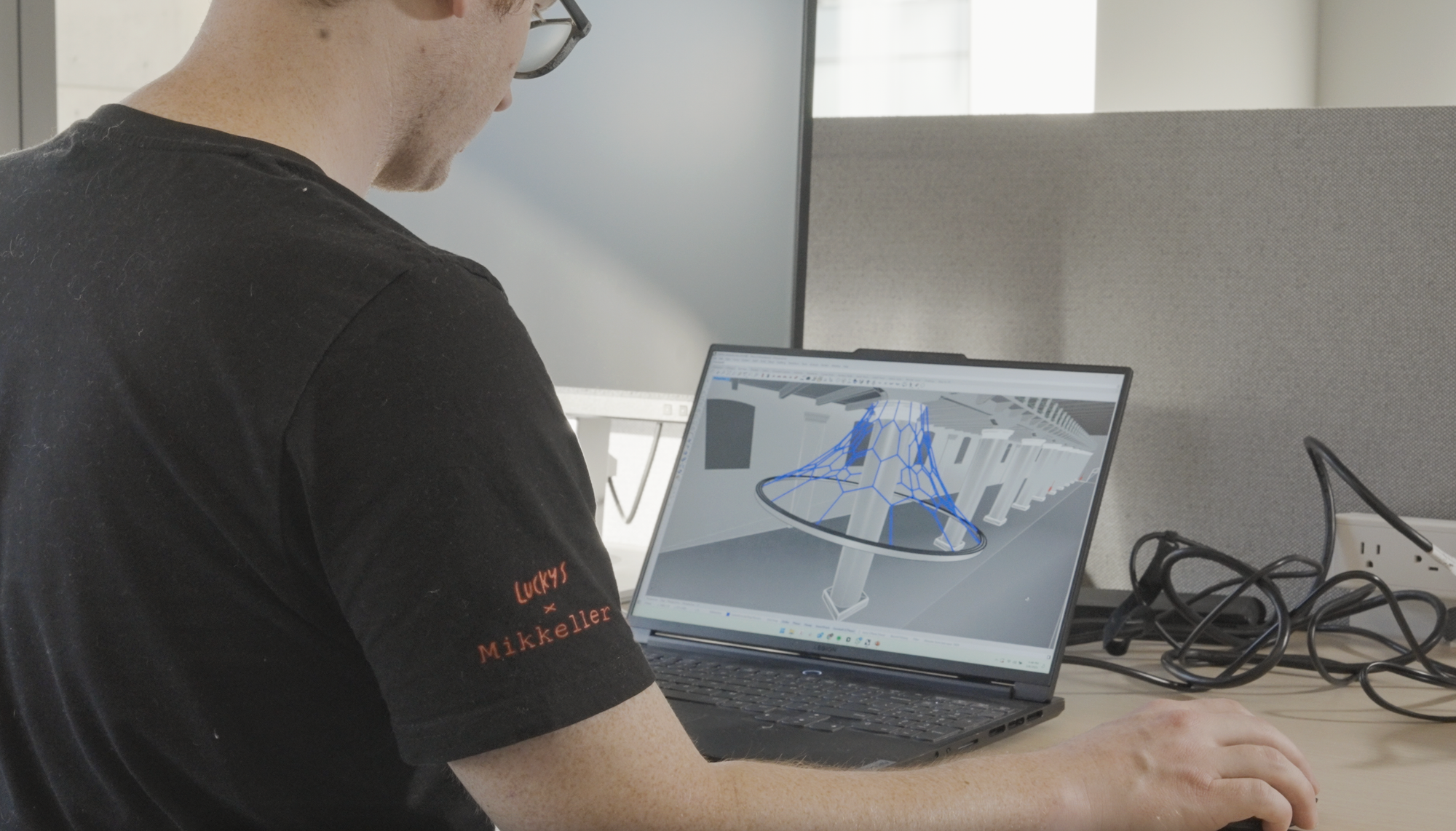

MIT Digital Structures research group led the design of structural geometries conditioned by materiality and gravity. “We knew we wanted to make a very large canopy,” said Mueller. “We wanted it to have anticlastic curvature suggestive of naturalistic forms. We wanted it to tilt up to one side to welcome people walking from the central corridor into the space. However, these effects are almost impossible to achieve with today's computational tools that are mostly focused on drawing rigid materials.”

In response, the team applied two custom digital tools, Ariadne and Theseus, developed in-house to enable a process of inverse form-finding; a way of discovering forms that achieve the experiential qualities of an architectural project based on the mechanical properties of the materials. These tools allowed the team to model three-dimensional design concepts and automatically adjust geometries to ensure that all elements were held in pure tension or compression.

“Using digital tools enhances our creativity by allowing us to choose between multiple different options and short-circuit a process that would have otherwise taken months,” said Mueller, “However, our process is also generative of conceptual thinking that extends beyond the tool — we’re constantly thinking about the natural and historic precedents that demonstrate the potential of these equilibrium structures.”

Digital Efficiency and Human Creativity

Lightweight enough to be carried as standard luggage, the hemp rope structure was spliced by hand and transported from Cambridge to Venice. Meanwhile, the heavier timber structure was constructed in Zurich where it could be transported by train — thereby significantly reducing the project’s overall carbon footprint.

The wooden rings were fabricated using salvaged beams and boards from two temporary buildings in Switzerland — the Huber and Music Pavilions — following a pedagogical approach that De Wolf has developed for the Digital Creativity for Circular Construction course at ETH Zurich. Each year, her students are tasked with disassembling a building due for demolition and using the materials to design a new structure. In the case of VAMO, the goal was to upcycle the wood while avoiding the use of chemicals, high-energy methods, or non-biodegradable components (such as metal screws or plastics).

“Our process embraces all three types of intelligence celebrated by the exhibition,” said De Wolf. “The natural intelligence of the materials selected for the structure and cladding; the artificial intelligence of digital tools empowering us to upcycle, design, and fabricate with these natural materials; and the crucial collective intelligence that unlocks possibilities of newly developed reused materials, made possible by the contributions of many hands and minds.”

For De Wolf, true creativity in digital design and construction requires a context-sensitive approach to identifying when and how such tools are best applied in relation to hands-on craftsmanship.

Through a process of collective evaluation, it was decided that the 20ft lower ring would be assembled with eight scarf joints using wedges and wooden pegs, thereby removing the need for metal screws. The scarf joints were crafted through 5-axis CNC milling; the smaller, dual-jointed upper ring was shaped and assembled by hand by Nicolas Petit-Barreau, founder of the Swiss woodwork company Anku, who applied his expertise in designing and building yurts, domes, and furniture to the VAMO project.

“While digital tools suited the repetitive joints of the lower ring, the upper ring’s two unique joints were more efficiently crafted by hand,” said Petit-Barreau. “When it comes to designing for circularity, we can learn a lot from time-honored building traditions. These methods were refined long before we had access to energy-intensive technologies — they also allow for the level of subtlety and responsiveness necessary when adapting to the irregularities of reused wood.”

A Material Palette for Circularity

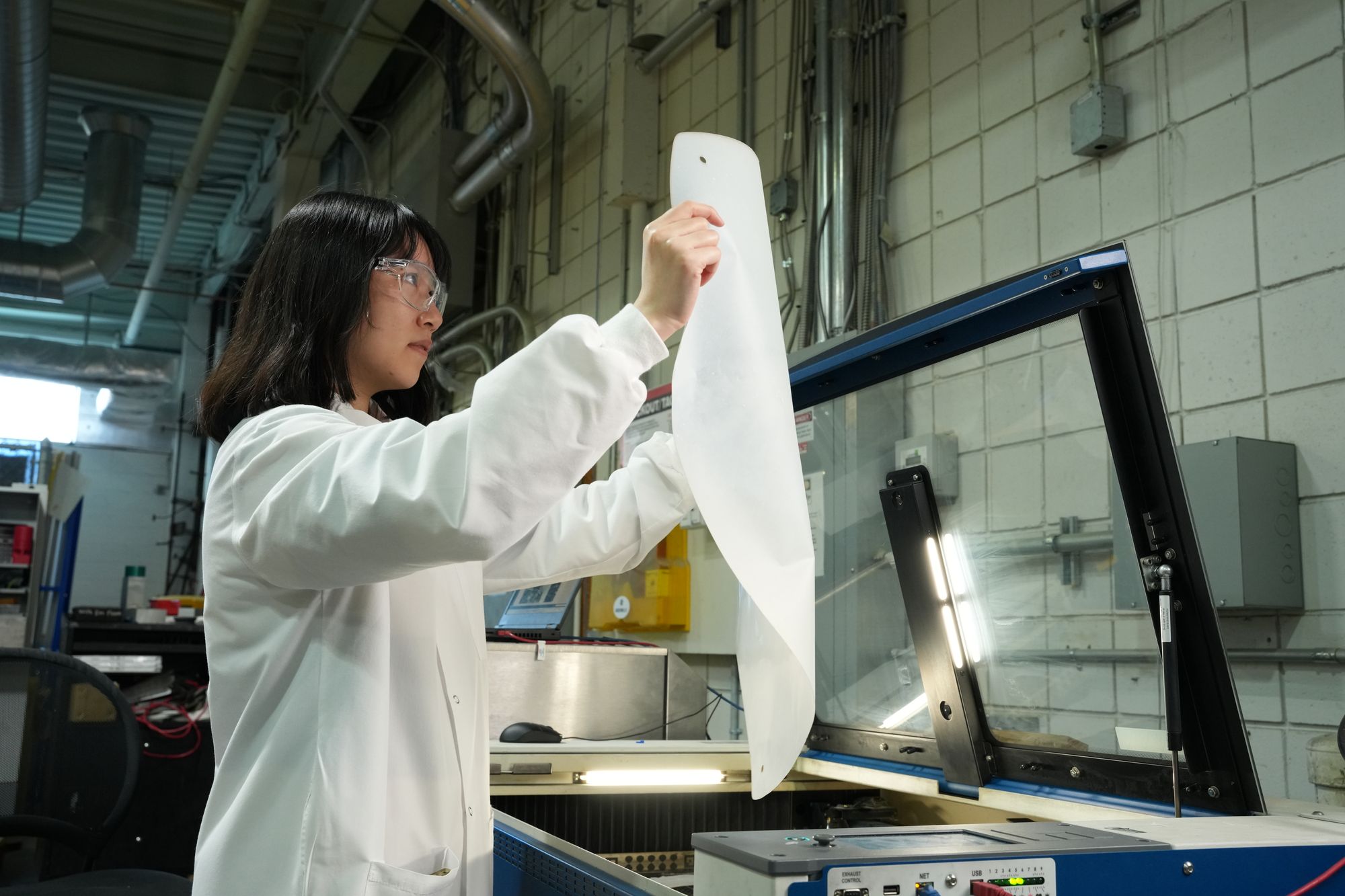

The structural system of a building is often the most energy-intensive; an impact dramatically mitigated by the collaborative design and fabrication process developed by MIT Digital Structures and ETH Circular Engineering for Architecture. The structure also serves to showcase panels made of biodegradable and low-energy materials — many of which were advanced through ventures supported by MITdesignX, a program dedicated to design innovation and entrepreneurship at MAD. Giuliano Picchi, advisor to the dean for scientific research on art and culture in the MIT School of Architecture and Planning, curated the selection of panel materials featured in the installation.

“In recent years, several MITdesignX teams have proposed ideas for new sustainable materials that might at first seem far-fetched,” said Gilad Rosenzweig, executive director of MITdesignX.

“For instance, using spent coffee grounds to create a leather-like material (Cortado), or creating compostable acoustic panels from coconut husks and reclaimed wool (Kokus). This reflects a major cultural shift in the architecture profession toward rethinking the way we build, but it’s not enough just to have an inventive idea. To achieve impact — to convert invention into innovation — teams have to prove that their concept is cost-effective, viable as a business, and scalable.”

Aligned with the ethos of MAD, MITdesignX assesses profit and productivity in terms of environmental and social sustainability. In addition to presenting the work of R&D teams involved in MITdesignX, VAMO also exhibits materials produced by collaborating teams at University of Pennsylvania’s Stuart Weitzman School of Design, Politecnico di Milano, and other partners such as Manteco.

The result is a composite structure that encapsulates multiple life spans within a diverse material palette of waste materials from vegetal, animal, and mineral forms. Panels of Ananasse™, a material made from pineapple peels developed by Vérabuccia®, preserve the fruit’s natural texture as a surface pattern, while rehub repurposes fragments of multicolored Murano glass into a flexible terrazzo-like material; COBI creates breathable shingles from coarse wool and beeswax, and DumoLab produces fuel-free 3D-printable wood panels. You can explore the full scope of new materials and fabrication strategies here.

The canopy showcases panels made of biodegradable and low-energy materials, many of which were advanced through ventures supported by MITdesignX, a program dedicated to design innovation and entrepreneurship at MAD.

Image: Adélaïde Zollinger

A purpose beyond permanence

Adriana Giorgis, a designer and teaching fellow in architecture at MIT, played a crucial role in bringing the parts of the project together. Her research explores the diverse network of factors that influence whether a building stands the test of time, and her insights helped to shape the collective understanding of long-term design thinking.

“As a point of connection between all the teams, helping to guide the design as well as serving as a project manager, I had the chance to see how my research applied at each level of the project,” Giorgis reflected.

“Braiding these different strands of thinking and ultimately helping to install the canopy on site brought forth a stronger idea about what it really means for a structure to have longevity. VAMO isn’t limited to its current form — it’s a way of carrying forward a powerful idea into contemporary and future practice.”

After the Biennale, VAMO will be disassembled, possibly reused for further exhibitions, and finally relocated to a natural reserve in Switzerland where the parts will be researched as they biodegrade.

Image: Adriana Giorgis

What’s next for VAMO? Neither the attempt at architectural permanence associated with built projects, nor the relegation to waste common to temporary installations. After the Biennale, VAMO will be disassembled, possibly reused for further exhibitions, and finally relocated to a natural reserve in Switzerland where the parts will be researched as they biodegrade. In this way, the lifespan of the project is extended beyond its initial purpose for human habitation and architectural experimentation, revealing the gradual material transformations constantly taking place in our built environment.

To quote Carlo Ratti’s Circular Economy Manifesto, the “lasting legacy” of VAMO is to “harness nature’s intelligence, where nothing is wasted.” Through a regenerative symbiosis of natural, artificial, and collective intelligence, could architectural thinking and practice expand to planetary proportions?

Credits

Computational form-finding

MIT’s Digital Structures research group, led by Prof. Caitlin Mueller; with the participation of Adam Burke, Adriana Giorgis, Carolina Meirelles R. S. Menezes, Prof. John Ochsendorf.

Material Upcycling

ETH Zurich’s Circular Engineering for Architecture research group, led by Prof. Catherine De Wolf; with the participation of Vanessa Costalonga, Clara Blum, Zain Karsan, Tim Cousin, Océane Durand-Maniclas, Roxanne Goldberg.

Woodcraft

Anku.ch, with the participation of Nicolas Petit-Barreau.

(Re)emerging materials

MITdesignX, led by Svafa Grönfeldt and Gilad Rosenzweig, with the participation of Giuliano Picchi; the MIT Morningside Academy for Design, led by Prof. John Ochsendorf; and MITdesignX Venice with local partner SerenDPT. Together, they supported the development and acceleration of teams such as COBI, Cortado, Hera Materials, Kokus, rehub, and Vérabuccia®. Additional materials teams who contributed panels include DumoLab Research (DLR), based at the University of Pennsylvania’s Stuart Weitzman School of Design, ReLea Core, based at the Politecnico di Milano, and Manteco, a leader in high-end circular textiles.

Expanded team

Noah Adriany, Jean-Nicolas Dackiw, Attilio Di Turi, Nate Ehrlich, Ioannis Galetakis, Chris Humphrey, Harish Karthick Vijay, Claudia La Valle, Nina Limbach, Meret Luginbühl, Ipek Mertan, Loukas Mettas, Ian Oggenfuss, Asena Özel, Reva Saksena, Dominik Stoll, Lauren Witte

Materials teams

Nazhla Alizadegan, Marco Arioli, Berfin Ataman, Massimiliano Banini, Eda Begum Birol, Jenny Cang, Barbara Del Curto, José Tomás Domínguez, Ian Erickson, Agar Firenzuola, Avigail Gilad, José Antonio González, Paloma González-Rojas, Vincent Jackow, Alexia Luo, Lee Marom, Behzad Modanloo, Laia Mogas-Soldevila, Fabrizio Moiani, Francesca Nori, Romina Pacheco, Mariapia Pedeferri, Bowen Qin, Luca Querci, Nicky Rhodes, Romina Santi, Booker Schelhaas, Matteo Silverio, Lucrezia Solofrano, Mattia Trovato, Baptiste Traca

Lighting

Special thanks to Targetti for providing VADER spotlights.

Related News

MAD Community Highlights at the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale

Jun 9, 2025

MIT Community at the Venice Architecture Biennale curated by Carlo Ratti

May 15, 2025

Greening roofs to boost climate resilience

Sep 20, 2023

Related Events

MAD at the Venice Biennale

Exhibition / Installation

May 10 – Nov 23, 2025

Global Commons and New Ecologies

Symposium

Apr 2 – Apr 3, 2025